Noor Murteza designs Dublin Arts Council’s self-guided booklets on fractals in nature

Growing up, Noor Murteza was fascinated by pattern, both natural and human-made. This fascination with pattern as an ornamental and design tool led to an MFA in Design Research and Development at Ohio State. In her PhD study, her research has progressed in questions around fractal patterning.

Fractals were first identified and described systematically by Benoit Mandelbrot in his 1982 book Fractal Geometry in Nature. He describes the geometry of nature as the roughness that exists prevalently in natural forms like in mountain ranges, in clouds, in tree branches and beyond.

Fractal patterns are self-similar patterns that repeat, scaling down or up as they repeat. The overall pattern, once repeated through several iterations, has more small components than big ones. As seen in the image of the fern, the small segment of the fern appears to be identical to the large fern, simply scaled down. This self-similarity is the main characteristic of a fractal pattern.

Interestingly, this patterning is prominent beyond the natural world of lightning, river deltas and ferns, and it can be seen as well in the human body. The networks of blood vessels, nephrons of the kidney and alveoli in the lungs all exhibit visually perceptible fractal patterns. Moving beyond what is visible to what is experiential, we see fractal patterns emerge in the examination of social group formation both virtually and in real life. It has been said that “the fractal nature of hierarchical organization of human society” is “deeply it is rooted in human psychology.”

This patterning is something we as humans expect to see, and the process of seeing it triggers associations of visual balance and feelings of wellness and ease in architectural spaces. Many have argued for the psychological, physiological and emotional wellbeing effects of being exposed to the natural environment. The biophilia hypothesis, posited by Edward Wilson, “holds that humans have an inherent affinity for the natural world.” Most notable is the research of Ulrich that showed surgical patients had shorter recovery times, requested fewer analgesics and had fewer complaints against the nursing staff when their recovery rooms overlooked trees and other flora. Various studies have put forward theories and evidence that fractal patterning might be at the root of these wellbeing responses to nature, and thus, exposure to fractal patterns has the same wellbeing effect.

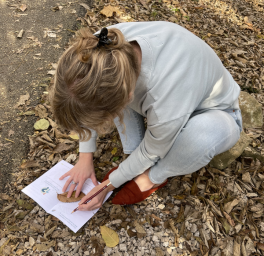

Murteza’s desire to merge the mathematical properties of fractals with design education has most recently emerged in her work with the Dublin Arts Council’s Patterns in Nature programming, where she has designed activity booklets filled with art and design-based activities intended to accompany walking tours in Dublin’s public parks. These books integrate STEAM through encouraging participants to notice fractal relationships within their experience of outdoor spaces with the hope that these activities of observation carry through to other environments. Enormously popular, these guidebooks work for a variety of age groups to teach the mathematical principles of fractals and to encourage spending more time outdoors, which supports community wellness. Patterns in Nature includes activities on doodling, pattern development, ephemeral land art and geometric leaf drawings.

Murteza intends to deepen her pedagogical practice as a design educator through further engagement with fractal patterns at the intersection of wellness and the natural environment. Soft copies of the booklets are available through the Dublin Art Council’s website and the QR Code.